The Cost to Take a Trip Around the World

I don’t know about you, but I’m incapable of reading about round the world trips without thinking in the back of my head, well that’s great, but how much did it cost?

The truth is, it depends. The title of this post is somewhat misleading. I can’t tell you how much it will cost you to travel around the world. I can only tell you how much it cost us to travel around the world. Everyone’s travel style and tolerance varies widely. Even in the realm of budget travel, there is a lot of variance. So much depends on things like the season, the country, the current economic state, and the strength of your local currency against the foreign currency, let alone personal factors like can you handle sharing a bathroom? Sleeping in a room with strangers? Taking cold water showers? Not having wi-fi? Going without a/c in the tropics? Taking public transport? Long haul bus rides? Eating on the street? Do you want to hop from country to country or city to city or do you like to stay in one place for a long time? Do you eat ramen to stay on budget or do you splurge on nice meals?

Besides travel style and other variables, the other thing to keep in mind when comparing long-term travel budgets is to determine what the numbers include. Some people include pre-trip costs like vaccinations and gear. Some people don’t. Some people include transport in their daily averages. Other people don’t, or only include certain types. Some people couch-surfed or stayed with friends, whereas others had to pay for all of their accommodations. What about things like prescriptions? Gear you pick up on the road? Travel insurance? Health insurance? Renter’s, home owner’s, or car insurance at home? Storage costs of keeping all your crap? Big ticket items like scuba certifications? Souvenirs for yourself? Holiday or birthday gifts for your family? Bills you have at home? Money you lost selling your home or your car at a reduced rate? There’s many direct and indirect costs that factor into how much a trip of this scale costs. When you’re checking out other people’s budgets, make sure you’re comparing apples to apples.

Even though I can’t tell you how much it costs to travel around the world, I’m sharing our numbers with you in the hopes that it may be a helpful starting point to someone who is trying to put together a budget. So without further ado, here’s our…

GRAND TOTAL

For the two of us to travel to 26 countries over thirteen and half months (409 days, to be precise), it cost us $71,897.46.

In this number, I’ve included the items that are most helpful for someone planning a budget:

– day to day costs (such as accommodation, meals, snacks, drinks, alcohol, activity fees, intercountry transport, tips, etc.);

– miscellaneous costs (laundry, ATM fees, exchange fees, gear and supplies picked up on the road, internet, etc.); and

– intracountry (i.e. cross-border) transport ($11,432.11).

I did not include the following items in the grand total. Many of these costs will vary widely based on your own situation. Plus, we didn’t track our pre-trip costs closely. When you are doing budget research, don’t forget to keep these costs in mind even if you don’t include them in your daily average estimate. Remember other people’s budgets may include some, none, or all of these things.

What’s not included:

– Student loan payments paid while we were away

– Minimal car insurance we kept on our car sitting at home

– Renter’s insurance for our items at home in storage (incidentally, I highly recommend looking into a renter’s insurance policy. It was cheap and turned out to cover items we brought abroad – like our stolen SLR. Our renter’s policy covered most of the loss when our World Nomads travel policy did not).

– Extra money saved as a buffer

– Cost of obtaining wills/power of attorney

– Costs of selling house/temporary housing

– Costs of selling house/stuff/car

– Costs of obtaining passports/passport photos/international drivers’ licenses

– Accountant fees for filing our tax returns while we were away

– Vaccinations, doctor co-pays for physician visits before we left, and prescriptions (guesstimate of about $2,500)

– Supplies & gear purchased before the trip (guesstimate of about $4,000 for everything except our SLR camera and camera gear)

– Storage for items we kept at home (about $1400 for the months we were away)

– High deductible health insurance we purchased to cover us in the United States (about $1,673 for the months we were away)

– World Nomads travel insurance ($1,113 for 12 months; we didn’t extend for the last 6 weeks)

– Scuba certifications ($1,201 for both of us to get our PADI certification in Koh Tao, Thailand and our advanced PADI certification in Perhentian Kecil, Malyasia)

– Gifts & souvenirs (about $2,100; includes our souvenirs, Christmas, birthday/Father’s Day/Mother’s Day/general gifts for family and friends, and shipping)

We’re pretty happy with our grand total. We never intended our budget to be firm and unyielding. Instead, we viewed it as more of a guide. We’re not the best budgeters, but it’s funny how lack of an income and a desire to keep traveling will keep you on track. We originally estimated $60,000. Had we not made the decision to add on 6 more weeks in New Zealand and Hawaii, our costs for our original plan of one year would have been about $62,710.

BUDGET IN CONTEXT

To put those numbers in context, we traveled with our budget in mind and watched expenditures, but we generally went for the best value instead of the absolute cheapest. This means, for example, that we might shell out an extra five dollars in Asia for a hotel room that was cleaner and brighter, or perhaps we would take a more expensive train instead of a bus if it got us there a lot faster. We always did our homework to be smart about our spending. We kept a close eye on ways to cut costs, like doing our own laundry when coin-op machines were available, or booking a service directly if it was just as easy to figure it out ourselves, or paying with a international fee-free credit card any place that would take it. We always had a private room and usually had private bathrooms, but from time to time we’d get a room with a shared bathroom if we were in a money saving mood. We sought out rooms with wi-fi and occasionally splurged on a/c. Because we love food and found food to be the way to the heart of a country, we ate almost all of our meals at a restaurant or on the street. We ate what the locals ate most of the time, but threw in some pricier Western style meals when we got sick of the local cuisine. We moved around a fair amount, and followed the weather even if it meant jumping around. We generally only flew when we had to, although we did take a few intercountry flights in India and one in Vietnam. We rented cars in a number of countries, but only compact or older cars. We didn’t shy away from doing activities even if they were costly, taking a when in Rome approach. (See, e.g. food and beer fest in Belgium; staying in a riad in Morocco and a ryokan in Japan; white-water rafting in Slovenia; cruising with Easy Riders in Vietnam; scuba diving in Thailand, Malaysia and Hawaii; taking a cooking class and visiting an elephant conservation center in Thailand; a candlelight tour of Petra; going up to the viewdeck on the world’s largest building in the UAE; getting up close and personal with whales in South Africa; going jetboating in New Zealand; etc.)

COUNTRY AVERAGES

There’s no doubt that WHERE you travel constitutes the biggest difference in your overall trip cost. Traveling through countries that are not as developed will drastically reduce your costs. We averaged $97.54 a day in countries that were generally less developed than at home – think of the type of places where cash is king. Our average was almost double in countries that were more developed, or about $190.69 a day. On the other hand, don’t assume that just because a country is less developed that it automatically is inexpensive. We found countries like Morocco and Jordan to be much pricier than countries like Laos and India (but much cheaper than countries like Spain and South Korea).

(Note: In order to give you an idea of what it costs to travel through different types of countries, these daily averages only include day to day costs (such as accommodation, meals, snacks, drinks, alcohol, activity fees, intercountry transport, tips, etc.) and miscellaneous costs (laundry, ATM fees, exchange fees, gear and supplies picked up on the road, internet, etc.). They do NOT include intracountry (i.e. cross-border) transport).

No big shocker here, but it was our experience that your dollar stretches the furthest in Southeast Asia, which is why we spent four months in that region. You really can get really nice rooms for $12-$25 (as long as you are willing to put up with your fair share of not so great rooms in the same price range, as quality can be somewhat inconsistent). And if you are willing to eat on the street (and hopefully you are, because the food is delicious and that’s how Southeast Asians eat), you really can get dinner for two for a couple of dollars. Our daily average in Southeast Asia was $81.70 a day, and it would have been possible to go much lower. Our daily average in Asia overall was $109.09 – flanked by a very expensive Japan on one end and a very cheap Laos on the other.

By sticking mostly to Central Europe, our European daily average was $175.92. (Note: our earlier post about European costs did not include intercountry transport, which is why those figures were lower).

Fiji – $53.48

- Total costs: $53.48

- # of days: 1

- Notes: We were only there for a long layover.

Laos – $59.82

- Total costs: $1,435.68

- # of days: 24

- Notes: The cheapest country for us!

Germany – $72.71

- Total costs: $218.12

- # of days: 3

- Notes: No lodging costs because we stayed with a friend.

South Korea – $74.10

- Total costs: $740.98

- # of days: 10

- Notes: No lodging costs for 7 days while we stayed with a friend.

Thailand – $80.44

- Total costs: $4,021.83

- # of days: 50

- Notes: Love Thailand! Includes travel through the islands during high season. We also did a lot of shopping/replenishing in Thailand so that is reflected in the cost.

Malaysia – $82.92

- Total costs: $1,243.84

- # of days: 15

- Notes: Similar in cost to Thailand, but we found lodging value to be better in Thailand. Transport in Malaysia tended to be nicer, though.

Cambodia – $91.53

- Total costs: $1,006.84

- # of days: 11

- Notes: Cambodia is pretty inexpensive, but two costs drove up the price somewhat: eating at restaurants where funds go to NGOs and fees for Angkor Wat.

Vietnam – $100.16

- Total costs: $2,504.03

- # of days: 25

- Notes: These costs drove up the price: one internal flight and guided tours (including a three day, two night Easy Rider tour, hiring a driver after Sean got sick to see the Vihn Moc Tunnels, and a mid-range overnight Halong Bay tour. Otherwise, Vietnam is a good value; you do get more for your money in lodging and food than the rest of SE Asia.

India – $107.09

- Total costs: $3,426.74

- # of days: 32

- Notes: India’s food and lodging are inexpensive. In fact, we found increasing your budget does not always bring a corresponding increase in quality. Costs are higher because we flew internally several times, including to the Andaman Islands.

Hungary – $108.78

- Total costs: $870.24

- # of days: 8

- Notes: Hungary is a good value in Europe!

Poland – $120.63

- Total costs: $482.50

- # of days: 4

- Notes: We only there for a short time, stayed solely in Krakow and ate pierogies most of the time.

UAE – $121.64

- Total costs: $243.28

- # of days: 2

- Notes: We were there twice. The first time, only to sleep in a hotel. The second time, we had a really long layover and went to the Burj Kalifa.

NYC – $129.74

- Total costs: $259.47

- # of days: 2

- Notes: This is for 2 days, one night. Our tiny hotel room alone was more than the daily average.

France – $130.54

- Total costs: $1,958.05

- # of days: 15

- Notes: No lodging costs except for one night in a B&B in Mont St. Michel and an air mattress because we stayed with a friend in Paris.

Czech Republic – $149.21

- Total costs: $1,193.71

- # of days: 8

- Notes: We were mainly in Prague, except for a day trip to Plzen. Costs tend to be higher in Prague, but you get a lot for your money. Beer is really cheaper than water here!

Jordan – $149.87

- Total costs: $1,348.84

- # of days: 9

- Notes: The activities in Jordan drive up the cost, especially the entrance fees to Petra.

Croatia – $161.39

- Total costs: $2,582.17

- # of days: 16

- Notes: This includes island hopping by ferry and a car we rented to go to Sean’s family’s hometown and Plitvice National Park. Food tended to be expensive (and average).

Slovenia – $175.83

- Total costs: $1,406.67

- # of days: 8

- Notes: This includes a car we rented for part of the time.

Morocco – $180.68

- Total costs: $2,710.17

- # of days: 15

- Notes: This includes a rental car and shady fees charged by the rental company.

Portugal – $186.78

- Total costs: $1,307.47

- # of days: 7

- Notes: This includes a rental car.

Northern Ireland – $195.51

- Total costs: $1,173.03

- # of days: 6

- Notes: This includes a rental car.

Spain – $202.83

- Total costs: $4,665.01

- # of days: 23

- Notes: This includes a rental car for a few days.

New Zealand – $205.03

- Total costs: $6,150.98

- # of days: 30

- Notes: Includes campervan rental in shoulder season. We did cook a lot, but when it rained for days on end, we ate out more than we planned to get us out of our campervan.

South Africa – $222.89

- Total costs: $6,017.93

- # of days: 27

- Notes: This includes a rental car.

Japan – $237.02

- Total costs: $7,110.45

- # of days: 30

- Notes: This includes a Japan Rail Pass.

Hawaii – $237.36

- Total costs: $2,136.22

- # of days: 9

- Notes: This includes a rental car.

Ireland – $261.03

- Total costs: $3,654.45

- # of days: 14

- Notes: This figure is estimated; we lost track of our budget quickly after many a round of Guinness. Costs are also higher because we rented a car and went out more than usual while our friends were visiting.

Belgium -$271.59

- Total costs: $543.17

- # of days: 2

- Notes: This just for a 2 day, one night trip to Brussels. Again, costs were probably higher because we drank a lot with our friend (alcohol will get you every time!) and bought an excessive amount of chocolate.

SETTING THE BUDGET AND MAKING IT HAPPEN

Traveling around the world sounds like a pipe dream, but all it takes is prioritizing travel above other things in your life, whether it be your car, your house, your wardrobe, your gadgets, etc. Getting Sean’s sweat equity out of our fixer-upper before we left was instrumental increasing our money stockpile, but so was living well below our means and several years of saving. If you want to do it – really want to do it in reality, not just in theory – you can make it happen. And you should make it happen. Because I can tell you, as much as it stung to find out in the middle of India that the sellers to whom we sold our house – you know, the one that we poured our hearts and souls into for four years – sold the house for $30,000 more less than a year after we sold it to them, the sting dissipates quickly when you realize, holy crap, I’m in India.

If you want to travel but don’t have the ability, desire, or time to save $60,000 or $70,000, don’t be scared by our numbers. It is absolutely possible to travel around the world for a long period of time for less than we spent. Check out two good round-ups of other traveler’s budgets here and here. If you want to or need to spend less, there are many ways to reduce the grand total. (And many ways to increase it, should you want to travel more extravagantly). For example, to cut costs, go for 11 months instead of a year. Go to fewer places for longer periods of time. Stick to countries that are less developed. Go in the off season. Skip pricey activities and stick to soaking up the atmosphere. Select accommodations where you can cook yourself. Consider couch-surfing. Don’t rent a car and take public transport. Limit the amount of fancy gear you buy in advance. There’s lots of ways to save, so don’t let money stop you from traveling. Prioritize what it important to you when traveling – location, accommodations, activities, comfort, value, lowest cost, weather – and the rest will fall into place.

We were fortunate to have enough money in the bank that we didn’t have to be slaves to our budget and could travel, for the most part, without money hindering our choices. We could have spent less, sure, but at this stage in our lives, we wanted a certain level of comfort and decided if we were going to do it, we might as well do it. And we could have spent more; there were times when we felt like spending a little more money would have allowed us to do more things or be more comfortable. But overall, we were happy with our style of travel and what it cost to travel that way. Because there are so many variables, setting your budget will not be an exact science. Once you have an idea of how much it cost other people to travel the world, you may want to pick a number that is feasible for you to save and that you feel comfortable with spending, and work from there to make your travels fit your number.

Hello to Fellow Fighters

If you’ve come from 1000 Places to Fight Before you Die, welcome! Mike and Luci, who tell what it is really like to travel as a couple on their blog, very kindly re-posted SurroundedbytheSound’s most recent blog post about race in South Africa over on their site. Mike and Luci also recently traveled through South Africa. They posted about their visit to Soweto Township, a place we didn’t get to visit, and about South Africa’s neighboring country, Swaziland, another place we would have liked to have seen but didn’t get a chance to. If you’ve never visited 1000 Places to Fight Before you Die, check it out!

Observations about Race in South Africa

I can’t help but always take note of race; it is a byproduct of being an employment discrimination lawyer, I suppose, where I was paid to analyze issues in racial terms. (And to my friend Tony – yes, I am mentioning race because it is relevant here).

Shortly before we traveled to South Africa, Karen Waldrond, one of my favorite writers and photographers, who I’ve mentioned recently, wrote that she believes that everyone should spend an extended amount of time outside of their home country, in a place where they are a visible member of the minority class at least once in their lifetime. I thought of her words while we were in South Africa. The percentage of blacks and whites in South Africa and the United States are roughly flipped: 79% of the population in South Africa are black, and 9.5% are white. 75% of the population in the United States are white, and 12.4% are black. (Of course, I realize the issue of race is more complex than black and white, but I am focusing upon the biggest majority group in each country). Early on in our trip, we walked into a crowded department store off of Long Street, a trendy street in downtown Cape Town, and realized we were the only white people in the store. This experience repeated itself again and again during our month in the country.

Being in the minority kept race on the forefront of my mind. Even more than that, the relatively recent fall of apartheid made it impossible to travel throughout South Africa without thinking about race. Like many of the other countries we have traveled through that have gone through significant historical transformations, it was fascinating to learn about what life was like before and what life was like now.

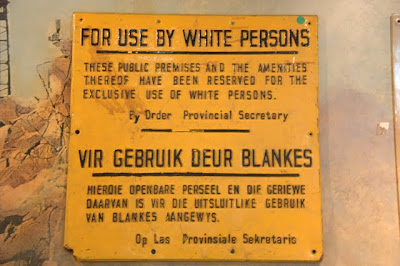

Apartheid – literally the state of being separate – was similar to segregation and Jim Crow laws in the United States, but much, much more extreme. And its official demise was only 16 years ago. Which means that during our lifetimes, blacks lived without the same rights as whites. And now blacks live with the same rights as whites, at least legally.

At the District Six Museum in Cape Town, we learned about the forced removal of 60,000 people from a neighborhood during apartheid. On our trip to Robben Island, the island where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 years, we learned a little about what prison was like directly from a former political prisoner. The most informative experience, by far, was the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. We’ve been to a lot of museums on this trip, and I felt this museum was the most educational and organized out of any of the ones we have visited. What I liked best was that you could choose to only read a brief overview of each section, or delve into the details should you so choose. The museum also packed an emotional impact just by presenting neutral facts. You are randomly assigned a race as you enter. I was white. Sean was “coloured” (a racial category used for people of mixed race that had more rights than blacks but much fewer rights than whites). This meant we were separated upon entrance and each had different experiences in the beginning of the museum. When we left the museum, together, we could peek back through a slit to see the entry point, where the races were separate. A reminder about how far the country has come.

The seven pillars of South Africa's current constitution displayed outside the Apartheid Museum: democracy, equality, reconciliation, diversity, responsibility, respect and freedom.

Renewing my education about apartheid made me scrutinize race relations much more closely than normal. I’ve read that the biggest issue today is the drastic differences between the haves and the have nots, and not the relations between the races.

This may be true, but I didn’t see any white people living in the townships and shantytowns on the outskirts of almost every city and town we drove through. At the beginning of our trip, it seemed like all of the owners, managers and patrons were white in all of the places where we stayed and ate, but the staff was black. Most of the suburban enclaves we saw were white, with the exception of maids. The rural, poorer towns we drove through had all black inhabitants. It wasn’t until East London and further north that we saw more upscale neighborhoods full of black people living and eating there. Finally, one of the B&Bs where we stayed was owned by a black person. But in these more upscale neighborhoods, we still didn’t see much integration between blacks and whites. In Johannesburg, we finally saw much more diversity. One of the places where we noticed this the most was at a secure suburban mall, where people of every race and color shopped and hung out.

Like crime, race is a sensitive topic in South Africa, so I only have my observations to go on. I always have the feeling that any observations are incomplete, and can only help facilitate learning more instead of being the final say on any particular topic when I travel. I’m not sure what all of my observations mean, but my suspicions are that the society has come a long way, but progress is slow. The fall of apartheid means that both a black and white cop can stand together and demand a bribe from two white people in lieu of a speeding ticket – thank goodness for progress, right? – but the effects of years of discrimination, oppression, and violence can’t be erased overnight or even in 16 years.

On Sprawl and Security

When people talk about South Africa being a beautiful country, they are talking about the natural beauty. After leaving architecturally rich Europe, it was quite a change to see squat, modern buildings radiating out without planning or foresight. In some ways, South Africa reminded us most of the United States out of all of the countries we’ve visited so far. The shopping malls, the need for a car, the suburban sprawl – it is all too familiar. But the sprawl in South Africa is more extreme, and what was quite different than home was the level of security. There are bars on the windows of McDonalds, even in a decent neighborhood. There are parking attendants on public streets and in private lots. Homes – and most of the guesthouses, backpackers, and B&Bs where we stayed – are hidden away in the suburbs behind tall concrete walls with coded gates and topped with electric fences. Particularly in Johannesburg, stores and restaurants – even grocery stores – are not located at street level. Instead, they are segregated away in shopping malls with pay lots. At home, you might see advertisements for home security systems, the type that might include a service to call the police if something goes amiss. In South Africa, you see advertisements for armed security, who promise to respond in minutes if there is a problem. At home, if we saw bars on the windows, we would assume we were in a bad area. In South Africa, the more bars, the better the neighborhood.

Compounding the over the top security is the way the country shuts down after dark (with the exception of Cape Town). Malls, stores, and grocery stores close shortly thereafter and people disappear from the streets. Many of the backpackers (hostels) are self-contained, serving dinner and alcohol so you don’t need to go out at night. Cars leave the roads (although we heard this is because there are few street lights and lots of people and animals roaming about). Towns would empty of the loiterers who had been hanging out doing nothing in the afternoons. It was winter while we were there, so it got dark around 6 p.m. We had a car, so we still typically went out to eat after dark (otherwise we would be taking early bird specials to the extreme), but we still were left with a lot of free time in the evenings. South Africans’ tendency to scurry inside as night falls was a strange thing to get used to after being in Europe, where we often wouldn’t venture out for dinner until 8 or 9 (even later in Spain).

All of the electric fences, security gates, and bars on windows made us recall some of the advice we had heard before we arrived. Shortly before we came to South Africa, we stayed at a B&B in Northern Ireland with an owner who was originally from Durban, South Africa. When she found out we were going to South Africa next, she gave us some advice. (1) Don’t wear lots of jewelry, she said, glancing at my necklace. (2) Always, always, always lock everything in your boot (trunk) and don’t leave anything in your car, even when you are in it. (3) In certain areas, you may need to run the robot (traffic light) instead of stopping. She went on to tell us about smash’n’grabs – when someone breaks your car window while you are stopped, reaches into the car, and grabs your things. She told us it had happened to her last time she was home. Someone reached in her car window and grabbed her purse right off her lap. She described how she chased him down because she was so mad something had been stolen from her again. The week before, someone had stolen her cell phone right of her pocket. By the time she was telling us about how credit cards charge people money to get a replacement card because everyone’s cards get stolen and not to feel sorry for the little kids who are sniffing glue and begging you for money, I was wondering what in the hell we were getting ourselves into. I know people can be alarmists, but this was someone from South Africa telling us it was bad.

What we were never able to figure out in our month in the country was whether the heightened security was a necessity, or part of a long ingrained culture of fear. Instead of making us feel safer, all of the security made us feel like we constantly needed to be on guard. I knew that an unfortunate side effect to the dismantling of apartheid is the development of one of the highest levels of crime in the world – most notably, violent crime. But I never could get a good read on how bad the crime really is. I don’t know whether the crime is indiscriminate, or maybe just confined to certain subsets of the population and to certain areas. Obviously nothing happened to us while we were there, and we didn’t see any crimes occur. And thousands of people travel to South Africa without incident. Honestly, if the security measures all around us hadn’t provided constant reminders, I probably wouldn’t have worried about crime at all.

While I loved the country, it is not a country in which I would ever chose to live. We certainly felt more at ease after our first day or so, but it is hard when you have constant reminders of what could take place. I would hate to live my life, sheltered away in a suburb, constantly looking behind you, as you drive from your fenced in home to the local mall to go grocery shopping. I don’t know. Maybe people who live there are more at ease and it is not that extreme for them. I would love to understand more about what it is really like for people who live there. Crime is a sensitive subject, especially in South Africa, because it is intertwined with race and apartheid and the haves and have nots, so it tended not to come up in conversation. Even when we tried to inquire with our accommodations about whether the area was safe to walk around, the answers were evasive and coy. We were always just given reminders to use standard precautions and to “be smart.”

Don’t get me wrong: we really loved our time in South Africa. Despite creation of my own jitters at times, I never felt unsafe, and I personally would not hesitate to travel there again. But for the foreseeable future, fear of crime is an unfortunate backdrop to any travels there.