The Vietnam War from a Different Perspective.

The Vietnam War, as we Americans call it, looms large in American history. Thousands and thousands died in the war on all sides. Many thought the United States’ involvement in Vietnam’s affairs was a mistake, and the opposition to the war defined a generation. Most people our parent’s age grew up watching footage of a far away land on the news; younger generations grew up watching movies dramatizing the Vietnam War.

While we were in Vietnam, we took the opportunity to try to learn more about the Vietnam War. Just being where the war actually took place opens your mind to a different perspective. War becomes a lot more real when you met the “other” face to face and see the places with your own eyes. It also allows you to learn things that American history classes at home leave out. For example, before traveling through Southeast Asia, I never knew that the United States’ involvement in Southeast Asian affairs extended far behind Vietnam and included extensive side bombings of Cambodia and Laos, as well as implicit support for the evil Khmer Rouge government.

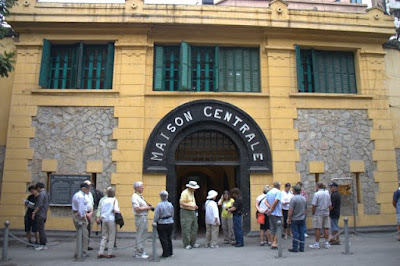

As part of our education, we visited a number of museums and exhibits. We toured the Reunification Palace, which is a time capsule of the way it was on the day the North Vietnamese army tanks rolled through the front gates in 1975 when the NVA finally captured Saigon; the War Remnants Museum, which tells the story of the Vietnam War from the perspective of the victors, i.e. the current socialist government; the Demilitarized Zone, the dividing line between North and South Vietnam; the Chu Choc tunnels, where a North Vietnamese village hid and lived underground for two years while bombs raged overhead; and the so-called Hanoi Hilton, where John McCain and other American prisoners of war were kept (and tortured) by the North Vietnamese.

As you can imagine, the current ruling Vietnamese government, as the victors of the war, have quite the different perspective on things. For starters, they don’t call it the Vietnam War; they call it the American War, or more bluntly, the American War of Imperialism. The War Remnants museum is peppered with references to the American aggressors and the South Vietnamese puppet government. It also shows many of the horrible effects of the war – but only those effects of acts committed by the Americans. Unfortunately, there is no shortage of acts to show.

All of the war related museums in Vietnam seemed to start out the same: with exhibits after exhibit showing the world’s opposition to the war. While there is no doubt there are many people worldwide that were opposed to the United States fighting in Vietnam, the captions on the pictures had their own spin, such as the one stating “American people demonstrated to support the Vietnamese struggle for independence and unification of the country.” Hmm, I could be wrong, but I don’t think that is quite what the Americans were protesting about.

The museums are full of references like these, to independence. At first, I was confused whose independence they were talking about. Whether the United States should or should not have gotten involved is a different matter, but I’ve always understood the war as being about the Americans and their allies fighting on behalf of the South Vietnamese to stop the North Vietnamese from spreading communism south. My wiser husband had to explain to me the obvious; from the current government’s perspective, they were liberating the South Vietnamese from the United States’ imperial ways and reuniting the country they never thought should have been divided.

Since the war-related museums were so extremely one sided, my antennae was up the whole time, and it was hard to trust what I was reading because I felt like much of the story was being left out or distorted. But, on the other hand, I felt there was an important lesson. How much of what we have learned in the past is incomplete or distorted? Learning about the war from the perspective of the Vietnamese government is a good reminder that there’s always more than one side to story: his side, her side, and the truth.

[Above: The Central Highlands hillside My told us the Americans bombed during the war.]

The awful Agent Orange exhibit, showing the effects of the chemical used by the Americans during the war. One of the more thought provoking things in the exhibit was a recent letter written to President Obama by a young Vietnamese girl affected by Agent Orange. The letter asks the United States for reparations for the effects of Agent Orange, which still affect the Vietnamese to this day. The United States has provided assistance to the soldiers afflicted with Agent Orange, but has not offered assistance to the Vietnamese, including the children fathered by American soldiers. Should they? Or is it just an unfortunate casualty of war? Food for thought.

Sean telling me to hurry up before the French tour group disappeared. The most cost effective way to see the Vinh Moc Tunnels is to see them on a tour of the DMZ from Hue. We were signed up for one, but Sean felt really sick right when we were supposed to leave at 6:30 in the morning. When he felt better later that morning, we decided to go just to the tunnels and do it on our own, since it was the one thing Sean really wanted to see in Vietnam. There is no public transport to the tunnels and they are some distance from Hue, so we ended up paying for the unused tour AND a pricey private car to the tunnels. The tunnels are clearly set up for tour groups, and the mainly Vietnamese speakers at the tunnels gave us conflicting instructions on whether we needed a guide or not to see them on our own. When the English speaking guide they promised never materialized, we ended up following a French speaking tour group into the very dark and very narrow tunnels.

Me in the Vinh Moc tunnels. As you can see, they are extremely squat and narrow - and dark. (Sidenote - our thighs hurt from squatting for days - how in the world did a whole village live down there for years?!?!?!) At first, the French group didn't notice us since we stayed well at the end. But then the tour guide started giving us weird looks, and he'd halfheartedly shine a light on us as he noticed us in the rear in the dark, trying to make our way down the pitch black stairs. Then, the whole group noticed us when they abruptly turned around. They declared something in French, presumably "turn around and go the other way." Or at least we hope it was that, and not, "who are these idiot Americans following us in the dark?"

Infamous picture of John McCain inside the Hanoi Hilton. This museum is full of references to the fun life the POWs lived while imprisoned. They learned more about the ways of the Vietnamese! They celebrated Christmas! They played sports! They got tortured! Oh yeah, the last one was conveniently left out.

Scenes from the South Island’s East Coast

So, do you want to get a look at all of this awesomeness we speak of, or what? The locals on the east coast kept telling us the real beauty is out west, but we think they’re just being modest. We found the east coast to be pretty fantastic, ourselves. Lots of coastline, lots of sheep, with a rainbow at the end? Yep, the east coast whetted our appetite, big time. (Above: The jaw dropping Banks Peninsula that first let us know what we were in for. Totally worth the detour from Christchurch.)

Months of chasing sunsets in the Southeast Asian islands with hit or miss results, and we get a stunner on night three in New Zealand without trying. Shot from the side of the road on the Banks Peninsula.

Good thing we took the scenic route marked with the tiny sign on the way to Dunedin, because we got to see this...

Apparently the autumn weather turned for the worse the day we arrived. Fantastic. It was so cold, even the horses needed coats.

Hog Tales, Vietnam Edition.

We didn’t plan on doing an Easy Rider tour, exactly, but when we wandered up to Dalat from Saigon, endorsements of others ringing in our ears, it was pretty much a foregone conclusion that we’d end up on the back of two stranger’s motorcycles, zooming through the Central Highlands. You don’t find the Easy Riders; they find you. In our case, My and his sidekick Mr. Pepperman found us as soon as we stepped off the bus. They’re part of the Dalat Bus Station Easy Rider gang. Neither official Easy Riders nor an official gang, they roll around town with emblemed jackets and work for the same boss, one Mr. Lee. Despite being accosted minutes after we arrived in Dalat, we didn’t hold it against My (pronounced Me). My didn’t give us the hard sell and he seemed like a nice guy. We thought about it for a day, then gave him a call. We negotiated a three day, two night trip through the Central Highlands from Dalat to Nha Trang for $61 a day, including accommodation and fees but not food, which we split down the middle. A fortune in Vietnam, but somehow we kept finding ourselves talked into tours and things we wouldn’t otherwise do in other countries. They’re good salespeople, those Vietnamese.

For three days, we zoomed around the Central Highlands on the back of their bikes, an interior region filled with mountains and forests and rice paddies. The motorcycles turned out to be much more comfortable than riding on the back of any of the scooters we’d taken, although by the end, our butts were ready to say good-bye. During our journey, we learned all about agriculture and now know where silk, coffee, rice, cocoa, sugarcane, tapioca, peppercorns, mushrooms, pineapples and rubber comes from. We saw three different waterfalls, a temple (of course!), a flower farm, and countless scenic overlooks. We watched people make silk, rice whisky, bricks, and rice paper. One night, we even slept on the floor in a wooden house on stilts in a minority village with a minority family (although curiously we never laid eyes on the family).

My promised us an insider’s look at Vietnamese culture, and for the most part, an insider’s look we got. He’d march us into people’s workplaces in the middle of their workdays and say, Ah-mee, where’s your camera, there’s a good picture over there. Then the next thing I’d know he’d be interrupting people’s work, posing photo ops, and My would be saying, Come here, Ah-mee, and I’d be wearing a conical hat or making rice paper or Sean would be pushing a wheelbarrow of bricks or driving a farm vehicle. Although we never fully got over the embarrassment of busting into someone’s life and taking pictures or regret that we were interrupting people in the middle of doing their really hard jobs, it was a side of everyday Vietnam we’d never be able to see without My and Mr. Pepperman. It was nice to be far, far away from the towns where everybody you talked to wanted to sell you something. For three days, no one tried to sell us anything.

In fact, because we were with My and Mr. Pepperman, we even got the local’s prices. More importantly, we got the local’s food. For each meal, they’d order dish after dish, and we got to try Vietnamese food outside of what appeared on the tourist menus. Some of the tastiest food we’ve had was during our Easy Rider tour, once I got over my food and utensils being touched. Back home, someone else touching your food would be rude, but in Asia, communal eating is the norm. Each meal would be begin with My selecting our chopsticks from the crock on the table and rubbing them down with the paper-like napkins to eliminate splinters. He’d clean our spoons, sometimes with his thumb, and organize all of the sauces. Then, we could begin eating. Communal eating doesn’t mean dishing food out with a clean spoon onto your plate to eat. No, communal eating means taking food from the common dish with your chopsticks, putting the food into your mouth, and taking some more food with the same chopsticks you just put in your mouth. And communal eating with My sometimes meant him taking food he with his chopsticks he thought you should have and putting it onto your plate. I suppose I should be glad he didn’t try to put it directly in my mouth.

We, too, were responsible for our share of cultural differences. I kept asking My if he’d fought in the war (thinking of the blurb in the guidebook about most of the Easy Riders being ex-Southern army men). Sean eventually kicked me and told me My was way too young to have fought in the war and I should quit asking because I wasn’t going to get any war stories. Which, really, was best. For one, it’s always good to have periodic reminders to kick preconceived notions out of your head. For two, it’s always a little awkward discussing war when your country was involved. Like when we stopped at an overlook, and My told us matter-of-factly, your country bombed this hillside and burned the whole thing down during the war. It’s kind of hard to formulate an appropriate response to that. Sorry just doesn’t seem to cut it.

Likewise when your Easy Rider guide apologizes for his county’s littering problem, or rather primitive bathrooms. One morning, after eating some tasty pho bo at a tasty roadside restaurant, I made my way back through the family’s home and used the restaurant’s bathroom, which doubles as the family’s bathroom. When I returned, My said he was sorry the bathrooms weren’t the same as what we were normally used to, and asked me what the bathrooms are like at home. Well, they usually flush by mechanics instead of pouring water down a hole, and uh, you don’t have to squat two inches off the ground or stand in a pool of let’s-pretend-it’s-water-not-pee to use them and, well, they have toilet paper and sinks with soap and hot water and, oh yeah, they’re not strewn with the proprietor’s dirty underwear or toothbrushes seemed like too much detail, so I just mumbled that they were a little different.

We’re not used to being around other people day in and day out besides each other, so My and Mr. Pepperman were an interesting addition to our traveling duo. As is usually the case with Easy Riders, My did most of the talking and Mr. Pepperman tagged along, eating an astonishing amount of peppers at every meal (hence his nickname) and every once in a while piping in with some broken English, like the time he showed us a picture of him as a young man fighting in Cambodia and bragging that he used big guns, big American guns! You never knew what was going to pop out of Mr. Pepperman’s mouth. Mr. Pepperman never stopped smiling during the entire three day trip, and as we’d come to learn, Mr. Pepperman comes prepared. At one of the lookout points, he suddenly busted out a warm can of Ba-Ba-Ba, a local beer, from his tiny bag and handed it to Sean, instructing him to drink. Later that night, after we’d finished dinner, he produced a guitar out of nowhere (albeit with only five strings) and crooned a series of ballads for the crowd.

My was much more talkative. When he wasn’t busy educating us on agriculture or telling us fun facts about the Central Highlands, he was practicing his skills as an amateur photographer – with my camera. Ah-mee, he’d say, give me your camera. This is a good shot! Sean and I had more pictures taken together as a couple during those three days than we did our entire trip. My’s favorite type of photos are jumping ones, and I could tell he had practice, as he got much higher than any of the rest of us. My periodically dropped us off to walk for a little bit, and on one of those walks, we came upon My and Mr. Pepperman posing for their own jumping photos, giggling up a storm.

Like anyone who has taken an Easy Rider tour before us, we found the three days to be a definite highlight of our travels in Vietnam. We saw beautiful scenery, got to know My and Mr. Pepperman, and saw Vietnam outside the tourism industry. If you’re thinking of going on an Easy Rider tour, do it. It’s definitely worth the money. We recommend My and Mr. Pepperman wholeheartedly. They were fun to hang out with, and very thoughtful, always making sure we were comfortable. They always went the extra mile, such as when they took us out to dinner in a cab to give us a rest from the bikes. We found them to be expert, safe drivers, which really, is the most important part. You can find My and Mr. Pepperman hanging around the Dalat bus station. Or they’ll find you.

My puts me to work too, much to my dismay at having to interrupt this women's work and borrowing her hat for a photo op.