Take Us Out to the Carp Game

We both used to be baseball fans. But sometime in the past 19 years, any love for baseball died. It is hard to care about baseball when generations of kids are growing up without seeing our home team win even just one more game than they lose, season after season; too many fans care about the pierogi races, fireworks, concerts, and fancy stadiums more than the game itself; the owners appear to have no desire to improve the team because losing still makes them money; and baseball in the United States is a business for big market teams instead of a sport for the people.

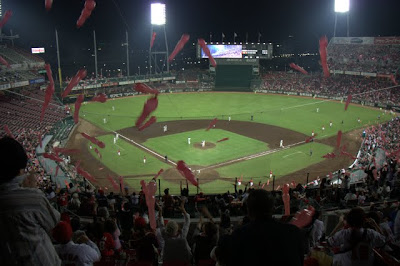

We’ve heard stories about the fervor and enthusiasm the Japanese fans can whip up for their teams. So while we were in Hiroshima, we decided to put our baseball cynicism aside and go root on the Hiroshima Carp.

We knew nothing about the Carp before we bought the tickets, but The Google informed us that we should feel right at home at the Carp game. Like the perpetually losing Pittsburgh Pirates, the Carp have serious winning problems. The Carp’s glory days were in the seventies, at least judging from the banners displayed in Mazda Zoom-Zoom Stadium. (Apparently corporate stadium names are also popular in Japan). But unlike the majority of Pirates fans (most notably excluding my ever-faithful Aunt Lynne, Uncle John, and cousins Karen and Johnny), the Carp fans have the ability to stay enthusiastic and hopeful during the entire game. And I mean the entire game.

I was doubtful that the Carp could be formidable opponents. Fish, even big ones like carp, just don’t sound that intimidating. Piranahas, maybe. Sharks, yes. But carp? And they seemed unoriginal, without rhyme or reason. Their logo emulates the logo of the Cincinnati Reds, but their mascot – notably, not a carp – is similar to the Philadelphia Phillies Fanatic (probably because the mascot was designed by the same firm). But we were in Hiroshima, so it’s root, root, root for the home team.

Before we got down to the business of rooting for the Carp, we checked out the vendors to see what was on offer. Happily, we found overpriced beer, nachos and hot dogs, because it just isn’t baseball without them. (Well, Sean was happy about the hot dogs; I wasn’t touching those with a ten feet pole. Who knows what goes in Japanese hot dogs?) Unhappily, our budget only allowed one beer, and let’s just say that the nachos and hot dogs are not the forte of the Japanese. We should have stuck with any of the other baseball classics. You know, sushi, edadme, and udon noodles. And let’s not forget the roaming tea vendor – our friend Danielle would be pleased.

Stomachs full, we turned our full attention to the game. Okay, we turned most of our attention to people watching, and partial attention to the game. There were Carp fans of all sizes, and many extended families taking it all in. The most fascinating part of the game was not the baseball; that was pretty much exactly like American baseball – long and drawn out with very few big plays, nine innings, a star player, and fair-ups. And a mobile Cup-of-Noodles for entertainment and corporate advertising between innings instead of the Mrs. T’s pierogie races. And, of course, a theme song played over and over with shots of the crowd on the jumble-tron. (The Carp theme song is the Inspector Gadget theme, in case you were wondering).

No, the most fascinating part of the game was the rapt attention the fans kept during all nine innings and their dogged persistence in repeating the same two or three chants over and over and over. Maybe it was because we didn’t know what they were saying, but it was amazing how many times the Carp fans repeated the same chants during the course of the game. When the Carp are at bat, the drum players in outfield cue the beat, and the Carp fans dutifully follow, chanting what I imagined was something like “Let’s Go Carp” and hitting two sticks together.

Okay, maybe everyone wasn't paying attention the whole time. This young Carp fan diligently hit sticks together for a while, but then started playing video games.

They didn’t let up the whole time the Carp were at bat. When the other team was up, it was their turn. The chants never died down, never were half-hearted, never sagged. Their tireless dedication was fascinating. And it paid off in a 1-0 shut-out for the Carp, with the pitcher pitching a complete game.

Peace

Visiting Hiroshima was hard. What made Hiroshima different than the other sites of former atrocities and hardships we’ve seen is that I somehow felt complicit, even though I wasn’t even born at the time America dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end World War II.

Even though it was always something I knew intellectually, visiting Hiroshima made it really hit home that we Americans should never forget that there are serious implications counterbalancing all of the freedoms and powers our country possesses.

But visiting Hiroshima, above anything else, was inspiring. Hiroshima’s Peace Museum doesn’t dwell on blame. I was impressed by the museum’s straightforward presentment of the facts: there was a World War; Japan was slow in admitting defeat; America dropped a nuclear bomb; much suffering occurred. People can debate what should have happened, whose fault it was, why it happened, whatever, but the museum gets right to the point. The people’s willingness to forgive Americans for causing all of the death, destruction and suffering was truly amazing.

What we saw in Hiroshima was that any anger towards a really, really negative event was turned around and redirected towards something positive: the goal of peace and the abolition of all nuclear weapons. Today, instead of hate and bitterness, peace radiates all over Hiroshima from the hypocenter where the bomb was dropped so many years ago. Everything in Hiroshima is about peace: from the peace signs the youth flash when posing for a picture in Peace Memorial Park, to Peace Memorial Park, to Peace Boulevard, to displays in the Peace Museum urging abolition of nuclear weapons.

What struck me the most were the rainbow of paper cranes, hanging from memorials and statues all over the city, but especially in Peace Memorial Park.

When I was younger, I remember reading a book about a girl who was slowly dying in the hospital from leukemia as a result of exposure to radiation ten years before. Before she died, the story goes, she was trying to craft 1,000 paper cranes for peace. In the book I read, she didn’t finish her goal, but her classmates jumped in to finish. I’ve heard alternate versions of the story where she did finish.

Today, people from all over the world are still making paper cranes and delivering them to be displayed in Hiroshima. Today, Hiroshima is not a horrible event from 1946; it is a real, living breathing place with vibrancy, resiliency, and strong, forgiving people. That’s not to say that people don’t still hurt and suffer, because they do, but they’ve chosen peace as a means to propel them forward.

Oleanders bloom all over the city. They said it would be years before vegetation grew back, but against all odds, the oleanders sprung up in the spring.

Sayonara to all our yen

[Editor’s note: Thanks for sticking with us while our access to internet was not up to snuff. I wrote lots of posts and processed tons of pictures, now I just need to get them uploaded. I’m hoping for some wifi in one of our rooms soon (wishful thinking) but I’ll do what I can with slow connections at internet cafes in the meantime, so stay tuned and please excuse me if I jump around a bit in the posts].

Japan was everything everyone said it would be: orderly, cutesy, polite, crowded, and expensive. Oh, was it ever expensive. We set a $200 a day budget for most developed countries we planned to visit. While normally we ended up being way under that amount, Japan was the first country where we had trouble sticking to the budget. To make matters worse, the value of the dollar kept dropping against the yen while we were there. It started at 83 yen to 1 USD, but dropped to 81 yen to 1 USD by the end. I suppose it negated any advantage we garnered from the weak euro while we were in Europe. If we hadn’t already committed to a three week railway pass and bought a plane ticket out of Tokyo to satisfy Japan’s proof of onward travel requirement, we would have left sooner. I enjoyed our time in Japan, but my enjoyment was tempered with ever-present concerns about our budget in the back of my mind.

(By the way, we were required to show our proof of onward travel when we entered Japan at the Fukuoka ferry terminal. We thought about trying some ways around the onward travel requirement, but since we already bought our rail pass, we bought our flight as well).

In the end, we ended up spending an average of $180.17 USD a day for both of us, not including transportation to and from overnight destinations. When that is added in, our costs were closer to $230. Keep in mind that our travel style is to travel as comfortable as we can at a budget level, so we occasionally splurge on things, eat out for almost all of our meals, and try to stay in private en-suite rooms.

To give you a sense of what you get for your money in Japan, here is a breakdown of the major expense categories:

Transportation:

I know one thing: you get what you pay for. Train travel in Japan is fabulous.

We rode the rails all around Japan, taking full advantage of our Japanese rail pass. (To read more about the logistics and costs of the rail pass, check out The Road Forks’ fantastically detailed post. In fact, while you are over there, check out all of their posts about Japan, especially their food posts breaking down Japanese eats with delicious photos). There is no need to upgrade to the first class green car; even the regular cars have tons of leg room and space for luggage. As someone who is perpetually trying to overcome my deep-ingrained bad habit of lateness, the oh-so-punctual trains blew my mind. The train stops were timed to the minute, meaning we relied upon the arrival time instead of trying to find the station name when getting off the trains. The trains zoomed around from city to city, making almost the whole country accessible by rail, and quickly. But all of this fabulousness comes at a price; it cost us $1500 for two three-week rail passes. We originally tracked the prices of the train trips we took, but stopped when we realized the passes paid for themselves only a week and a half into their use. We occasionally had to supplement our travel costs with local non-JR trains, but they usually were no more than the cost of a subway.

Speaking of subways, those too were more expensive than other major cities, such as Seoul. Part of the problem in Tokyo is that there are two different entities running the lines, meaning that sometimes you had to pay for two tickets to get the whole way where you were going. Since Tokyo is so big, it doesn’t really matter where you stay, but try to stay in walking distance to both lines to minimize costs. If you can’t do that, I’d choose something near the Tokyo subway line, since most things you’ll probably want to see fall on the Tokyo lines.

Accommodation:

We quickly learned that you don’t get a lot for your money in Japan. It wasn’t out of the question for a private room in a hostel with a shared bath to be nearly 8,300 yen (about $100 USD), although ones in the 6,225 yen (about $75 USD) range exist. Hostels tend to be Japanese style, meaning that you sleep on futons on a tatami-mat covered floor and take your shoes off at the front door. Dingy rooms, unpleasant smells, and shared bathrooms are common, but luckily so is free wi-fi.

We found business hotels to be a better value than hostels in the cities. Business hotels have plain, basic, boring rooms with the same exact features that all look exactly the same – the type of unimaginative hotel room I hate when on vacation but appreciate for its consistency on the road.

In Japan, a business hotel generally will get you a pretty small but clean room with fast hard-wired internet, a flat-screen television with one or two English speaking channels, decently cheap coin laundry, a refrigerator, a plastic pre-fab en-suite bathroom complete with a fancy electronic toilet, free Japanese breakfast, a cold filtered water dispenser in the lobby, and a hard double bed with strange beanbag pillows.

Toyoko Inns are ubiquitous throughout Japan’s cities. Since we ended up spending a fair amount of time in Kyoto and Tokyo, we bought a Toyoko Inn membership for something like $18 USD. The membership gets you 30% off on Sundays and holidays, 20% off on Mondays, and a free single room after 10 nights. If you opt to not have your room cleaned every day, you can also save 200 yen per day for certain days. (Be forwarned that on days you do have your room cleaned, the staff get very upset if you don’t leave your room between 10 and 2, the cleaning hours. We learned this the hard way). Depending on when your stay falls, the rooms can work out to be pretty cheap for Japan even with the cost of the membership. For us, after factoring in all the different type of discounts and membership fee, the average cost per night for our 8 nights in Kyoto and 9 nights in Tokyo was about 6469 yen (about $77.94 USD).

Food and Drink:

Food and drink is another category where Japan can empty your wallet if you are not careful. Unlike some other countries where we have travelled, the Japanese are great with promptly refilling your ice water at restaurants. This is a good thing because we mostly couldn’t afford to drink anything else. Soft drinks were typically about 400 yen (close to $5 USD) in restaurants, making them cost-prohibitive. Sean occasionally splurged and got Cokes out of the vending machines, where a can could be bought for 100 to 150 yen ($1.20 to $1.80). Beers were even worse. A Japanese beer like Kirin, Sapporo, or Asahi, was usually 600 or 700 yen in restaurants and bars ($7.22 to $8.43 USD), making Japan mostly a dry month for us. One night, we splurged in Tokyo and visited Baird Brewing’s taproom, which is a bar featuring the beers of the Japanese microbrew. The beers were great – probably the best we’ve had since Europe – but the whopping 900 yen for a pint was hard to stomach. That’s almost $11.00 USD! At least it turned out that it was for charity. The night we visited, Baird Brewing donated 100 yen for every drink purchased to Room to Read, a charity donating books to children in impoverished African and Asian countries. If you want to get your drink on, vending machines are where it is at – there, a can of beer is 300 yen ($3.61 USD).

One of the problems with budget travel in Japan is the temptations around every corner. Japanese food was tasty for the most part, but it is very foreign to our American palates, making us susceptible to influences. The Japanese love high-end status items, and this includes food. For example, although Japan is a tea drinking nation, they are very into coffee, especially of the iced variety. The multitude of Starbucks proved to be too tempting to us, especially for Sean the coffee lover. We tried to stay away, but dropped 420 yen (over $5) on coffee too many times. We also tried the local coffee chains, but those weren’t priced any better.

For my part, the sweets were the culprit. No matter how many times I told myself not to succumb to the chocolate cake behind swanky department store counters or in trendy cafes because it just didn’t taste right, I did it anyway. And I had been counting down the days to Tokyo since we finished the Pierre Marcolini chocolate I bought in Belgium. My research had revealed that Pierre Marcolini is sold in Japan, but what I didn’t know was that it was priced over four times as high as it was in Belgium. Four times! It was a sad, sad day when we visited the Ginza Pierre Marcolini store and I learned that the $7 gourmet tablets of chocolate I bought in Belgium were priced at $28. While the Japanese around us walked out with bagfuls, I resigned myself to eating one tiny $4 piece, delivered to me in an elaborate box even though I could have popped it in my mouth right then and there and saved everyone a lot of trouble. I stretched it for as long as I could to get my $4 worth, but couldn’t make it last more than two bites.

But of course, you need more than overpriced coffee and chocolate for substance. If a lunch or a dinner was $25, we considered that to be a bargain in Japan. My favorite “cheap” place to eat was the bottom floor of department stores. There, you will find counter after counter of prepared food. It can be a sensory overload, because the options are endless (Noodles? Gyoza? Sushi? Fried chicken? Salads? French food? Chinese food? Thai food? Dessert?) The female counter clerks call out in a sing-songy high-pitched voice in Japanese trying to entice you to their counter. The bento boxes, designed to be a portable meal on trains, were usually the best value. My favorites were the different Japanese salads, gyoza, sushi rolls, or Thai spring rolls.

We also saved money because breakfast was included in the price of most of our rooms. While I can never get used to the idea of eating savory dinner items for breakfast, and while we got sick of eating the same meal over and over, the rice balls and toast at the Toyoko Inn’s included breakfast was filling and prevented us from dropping $17 USD on coffees and muffins at Starbucks or other cafes.

In the end…

…I still think Japan is worth a visit. You just need to be mindful of your costs while you are there. If we had to do it over again, we would have spent only 2 or 3 weeks in the country and got a 14 day rail pass. Japan is just too expensive to dawdle on a trip like ours, and because of the efficiency of the railways, you can hit a lot in two weeks. We spent a lot of time in Tokyo and Kyoto – over a week in each – which definitely could be cut down. We had planned to do a lot of day trips from Kyoto, but didn’t end up making any of them except one half day to Kobe because of various reasons (rain, migraines, etc.) We got a little bored in Kyoto, but not in Tokyo, so it is all personal preference, I suppose. Even if you are not normally a planner, be organized and efficient like the Japanese and plan your trip before you enter the country to maximize your time and money. Hyperdia.com will be your best friend. It is a great tool that allows you to access the train schedules for all companies in English. There is a lot to see in Japan, so just decide what appeals to you the most – the cities, the “countryside” (to the extent there are rural areas in Japan; the “rural” areas we visited ended up being mostly smaller, low-key cities); mountains; temples and shrines; historic Japan; or modern Japan.